Our Crumbling Foundation: How We Solve Canada’s Housing Crisis, is a book by BC based journalist Gregor Craigie on the housing crisis in Canada. I really enjoyed this book for how many great ideas it provided for making housing more affordable.

The Ottawa Urbanism Book Club will be discussing Our Crumbling Foundation on Tuesday August 27 at 6:15pm at Sunnyside Library, and we’re also hosting a virtual author Q&A on September 9 (message me for the link).

Here are 6 things Ottawa can learn from Our Crumbling Foundation:

1. Many solutions are needed to solve the housing crisis

The biggest takeaway from Our Crumbling Foundation is that there is no one solution to the housing crisis. From investing more in public housing, to improving transit, to increasing the supply of private market units and making it easier to build the right kind of housing, many levers and strategies will play a role in making housing more affordable.

2. Invest in public housing for everyone

Craigie talks about Paris, which makes a concerted effort to build much more affordable housing. In 2017, more than 98,000 new homes were built in Paris, one-third of which were social housing units. By comparison, New York City built 20,000 new housing units and London built only 19,000 in 2017 (p. 46).

The sheer number of homes, and social housing units that Paris built was impressive, but what catches my attention is how social housing is not only built for the poorest people. Craigie talks about a converted department store with housing on top, where a recently divorced teacher moves after having trouble finding housing.

Providing social housing to more middle class people can do wonders for quality of life and provides everyone with more negotiating leverage, even when looking for housing on the private market. It helps to level off the price as a more affordable option is potentially available elsewhere.

3. “Housing first” saves money

Ottawa has a huge homelessness crisis, and the “housing first” solution that Finland uses is something we should definitely consider.

Housing first is when housing is provided unconditionally to the homeless or addicted, regardless of if they use or not. Juha Kaakinen, the CEO of Finland’s housing non-profit Y-Foundation explained: “To say, ‘Look you don’t need to solve your problems before you get a home.’ instead, a home should be the secure foundation that makes it easier to solve your problems.” (page 90)

This definitely sounds like a better way for our homeless to live, and also like it would keep our streets a lot cleaner and safer, but what intrigues me the most is the potential cost savings. “The Y foundation claims that moving one chronically homeless person into stable housing saves the government around €15,000 a year in social costs.”

Medicine Hat, Alberta has also adopted the housing first strategy. Considering our poor financial situation and the sadly high number of homeless people in Ottawa, I think it’s worth considering for us.

4. Supply and demand matters

Despite how important public housing investments are, in Canada the private market will always play a large role in providing housing. This means that to improve vacancy rates and reduce rents we need to make it quicker and easier for the private market to build the right kind of housing.

Craigie provides BC as a positive example of increasing housing supply, reducing municipal zoning restrictions and encouraging upzoning, quoting BC Premier David Eby saying: “I can understand you don't want a shadow on your property… or you’re concerned about parking. But at the same time… you’re wondering why local stores are struggling, and you wonder why your taxes are going up because the expansion is happening out in the suburbs insead of downtown areas,” (page 14)

About Here, a BC Based creator, has a great Youtube video explaining why private housing supply matters.

Ottawa should learn from this and be more ambitious in their draft zoning by-law. Although the draft zoning by-law allows 4 units as of right, meaning any lot can theoretically be converted into a fourplex, city staff estimate a turnover rate of redevelopment of only 0.5% per year across the entire city.

If affordability and higher supply is the true goal for Ottawa, we should be aiming for more frequent gentle density, which will be addressed in the next point.

5. Make building easier

Things like setbacks and long permitting times make it so that theoretically good projects that increase supply don’t actually pencil out or aren’t possible in the real world.

Craigie talks about a developer in Victoria, BC who calculated that with minimum building heights and setbacks, “they couldn’t build a house plex on a lot that could be profitable for the company at the price that would sell on the local market” (page 168).

Reducing setbacks also does wonders for making an area more walkable and cozy feeling.

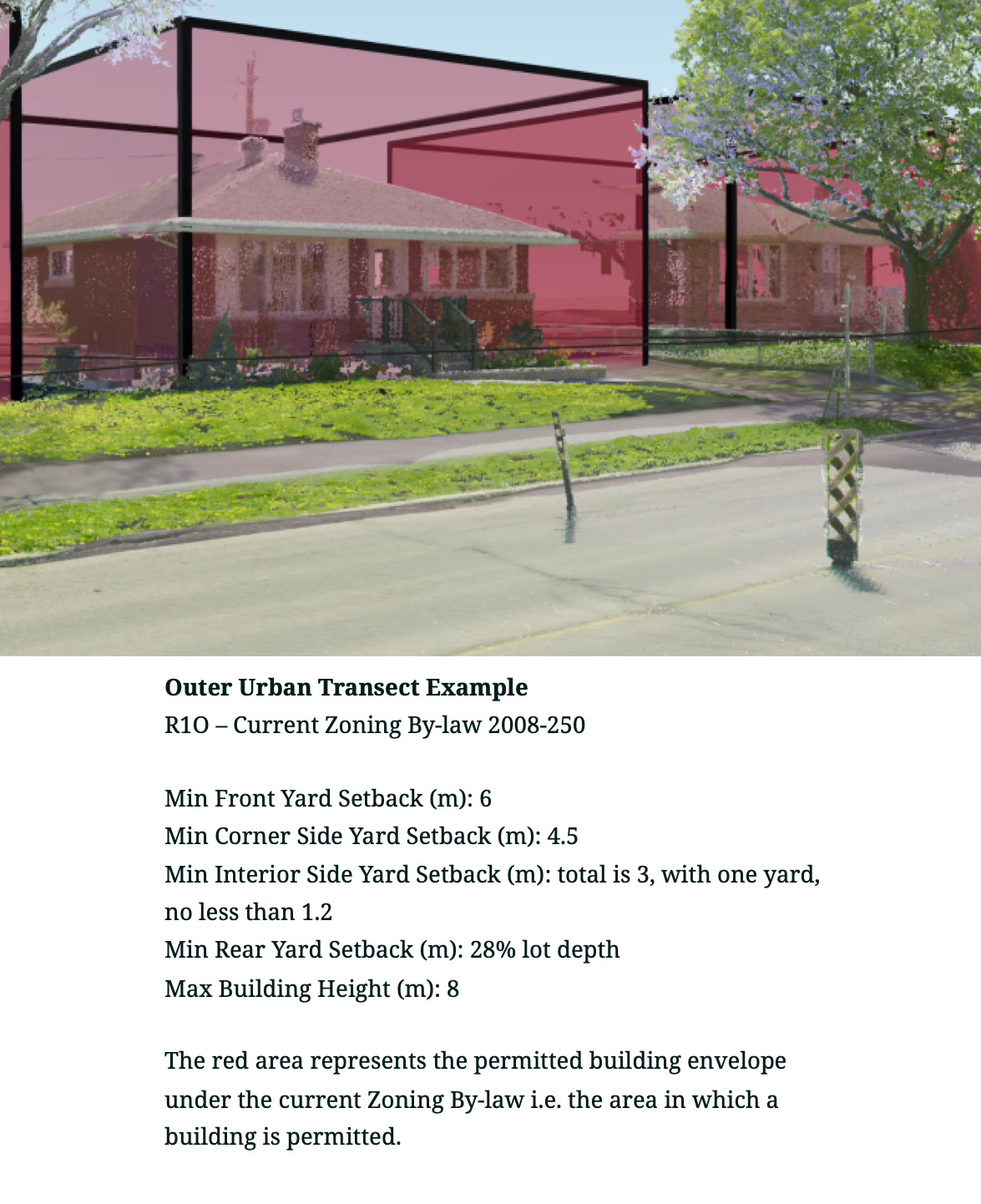

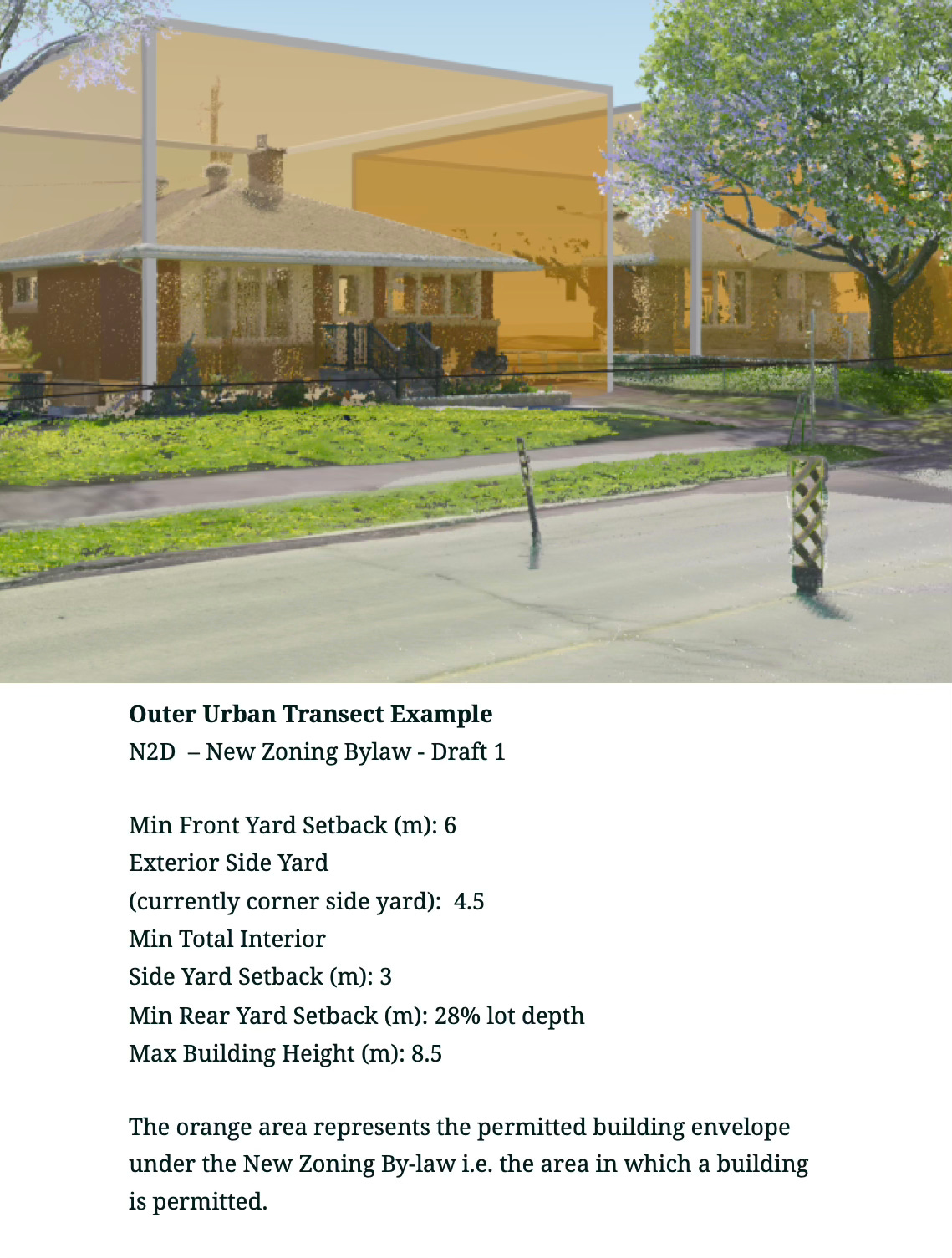

Unfortunately, Ottawa’s draft zoning laws don’t appear to be much of an improvement when it comes to certain roadblocks like setbacks.

Below are an example of the current zoning (first picture in red) and new draft zoning (second picture in yellow) for the outer urban transect. As you can see, the setback is basically the same as before, and the maximum height is just .5 metres taller.

6. Transit and housing are interlinked

There are so many benefits to properly planning housing and transit together. Craigie talks about Japan, where living is made more convenient and affordable due to frequent and fast rail connections. André Sorensen a professor of geography and planning at the University of Toronto is quoted in the book: “Japan’s public transit and the railway system are so convenient. It opens up lots of sites. Even if you’re in a big city, you can get to where you need to be conveniently and cheaply.” (page 22)

When housing and transit are properly planned together it’s easier for residents to live without a car, or to go from owning two cars to one, providing additional cost savings. It also means that more land can be used for housing instead of car storage.

Ottawa should ensure that all new transit, especially BRT and LRT, is closely linked with dense housing. This means not building LRT stations in the middle of the highway on any new projects or expansions. It also means that housing projects like Tewin, which won’t connect well with transit, should probably be reconsidered.

Thank you for reading and please consider sharing with a friend if you enjoyed.